Disclaimer: I am not a planner or an architect, but I did stay at a Holiday Inn Express last night. Wherever you notice any errors or wrong assumptions, please let me know.

Introduction

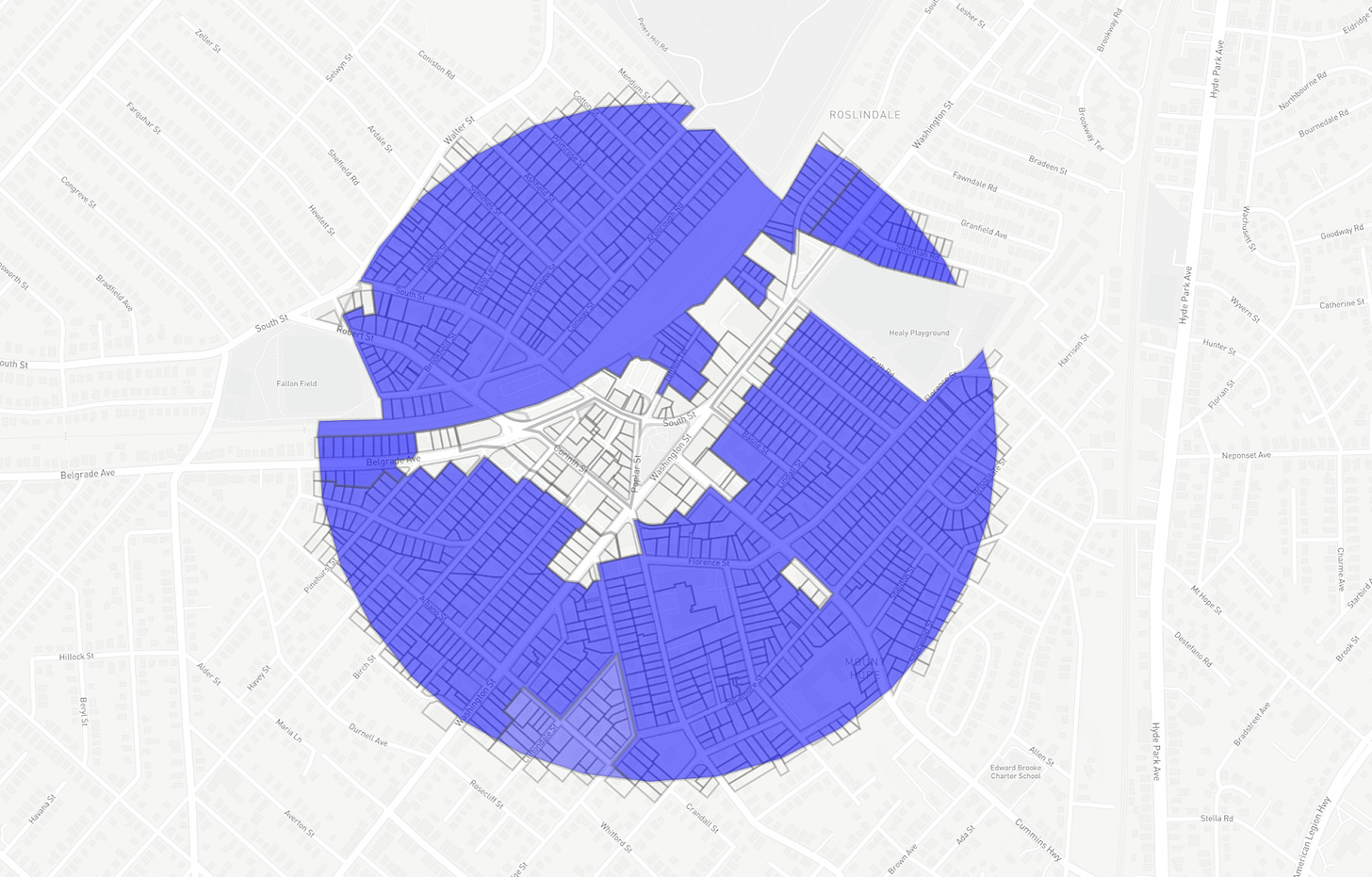

Roslindale Square is one of the first two sites of the Squares + Streets zoning initiative to encourage more housing and mixed-use development near transit and main streets. The final step for Roslindale will be an update to its zoning map, which will happen by the end of the year.

This week, the Boston Planning Department (formerly BPDA) will present its first zoning map recommendations for a ⅓ mile circle around Roslindale Square.

I expect that the bulk of the new zoning will concentrate along the main corridors of Washington, Cummins, South, and Belgrade. This is a great place to start, but it would be a big missed opportunity not to rezone the residential streets, too.

Specifically, I’d like to see the S0 “Transition Residential” district applied to all streets currently zoned for one-, two-, and three-family homes, which make up the vast majority of the Squares + Streets area.1 Mapping the S0 district could result in 520 new homes and welcome 1,200 new neighbors over the next decade.2

Applying the S0 to residential streets will benefit existing homeowners by granting them significant property rights and slowing the growth of property taxes.

The S0 is also a smarter way to thicken up our neighborhood. A fairly typical planning approach to adding housing in a community is to lump it all into the busiest areas. While this may get the job done, so to speak, it can also exacerbate the problems that growth-resistant residents bemoan the most: crowding, parking, and traffic. Taking a rising tide approach to growth can minimize these effects by distributing them more evenly.

Finally, applying the S0 is the right thing to do, because it will help us add more desperately needed homes, it will diversify our neighborhood by diversifying our housing (think triple-deckers, townhomes, and small condo and apartment buildings, not towers), and it will help our city better adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Ok, I can already hear your groans:

“That’s a terrible idea. The crowding. The parking!”

“What the hell is an S0?”

In this essay, I unpack the jargon around the S0, and then paint a picture of how our residential areas may change under it: the kinds of buildings we’ll see; when and where they’re built; and what their impacts will be. I am convinced, and hope you will be too, that these changes will benefit both future and existing Rozzidents.

Addressing questions and concerns about the S0

What’s an S0 district?

If the Planning Department mapped the S0 district to your street, that would technically permit a homeowner to build up to 4 stories with 14 units of housing on their lot without needing a variance. But there’s a big difference between what’s technically allowed and what’s effectively allowed.

In most cases, the S0 effectively permits a homeowner to build 3 stories with 6 units of housing without needing a variance due to zoning’s interaction with other housing policies, building codes, and lot size.

Let’s look at some of these factors whittling down what’s feasible under S0:

Boston’s updated Inclusionary Development Policy (IDP), which goes into effect October 2024, requires that new buildings with 7 or more homes set aside 17% of as income-restricted to households earning 60% of Area Median Income, plus another 3% of homes set aside for housing voucher holders. A tradeoff of this laudable policy is that market rate developers aren’t going to build many multifamily buildings with 7-14 homes (the max permitted under S0), because they simply can’t make enough margin on the market rate homes for the project to make financial sense. Instead, we will see an increasing number of small multifamily buildings with 6 or fewer units. If you don’t believe me, ask any small residential developer or off-duty urban planner. Few people discuss this publicly, but inclusionary zoning results in fewer homes being built.

Elevators! The building code requires that residential buildings taller than three stories have an elevator. Between the added cost and the floor space that elevators eat up, it’s not worthwhile to build 4-story buildings with so few units.

Lot size. If you look at a 4,000 square foot lot, which is typical for the Roslindale Square area, the maximum floorplate allowed by S0 is 2,000 square feet. If the lot is developed with any parking, then the floorplate will need to shrink accordingly, and so will the number and/or size of homes in the building.

What would new developments under S0 look like?

Under S0 zoning, we’d see more 4-6 plexes built over the next 10 years, along with some small apartment buildings. Some of these will be new infill development, while a good number will be redeveloped single- and two-family homes. I think it helps to visualize these buildings and how they’d fit into the neighborhood, so I’ve included a few examples below.

The small 6-plex

This building on 16-18 Hewlett Street lies on a 5,000-square foot lot in an area currently zoned for two-family homes. The building has six 800-square foot condos, and fits nicely within the context of the neighborhood. The smaller home size contributes to their relative affordability for the neighborhood ($450K vs. $660K median sale price April ‘24). This is a great example of what gentle density can achieve: more homes and greater affordability while maintaining the neighborhood feel.

The big 6-plex

Now let’s consider another scenario on the same parcel, but where a developer takes full advantage of the allowed building footprint so that they can build larger condos more suitable for families. It has the same frontage, but a smaller backyard. Does it still fit within the context of the neighborhood? Sure.

The cute 4-plex

Another example development we may see more of are 4-plex condos with 700-800-square foot units like this cute building a stone’s throw from Fallon Field. Does it fit in the context of the neighborhood? Well, I’ve walked by this building a hundred times and only noticed that it was a 4-plex when I started scouting sites for this piece.

The small income-restricted apartment building

A crucial exception to the effective cap on 6-unit buildings is when a project is actually intended for affordable housing. For practical purposes, the City defines an affordable housing development as one where at least 60% of the units are income-restricted at 100% of Area Median Income (AMI) or below.

Affordable housing developers are significant contributors to Boston’s housing supply, having built 21% of new homes in the last decade. The S0 may create an interesting opportunity for introducing greater affordability to our residential areas with 4-14 home apartment buildings.3

Given the lot size constraints, some developers may pursue a Single Room Occupancy (SRO) building, which offers affordable homes to single adults with a private bedroom and shared facilities. Some, but not all, SROs serve targeted populations such as individuals in recovery, survivors of domestic violence, and veterans.

The compact living building

A few years back, the City launched a Compact Living Pilot to test the idea that building smaller-than-usual homes could be a path to greater affordability and sustainability.

Perhaps the most ambitious project under this pilot is 141westville in Dorchester, a 4-story, 14-unit building of 280 sq ft studio apartments costing $750/month (most utilities included). It is living proof that “market rate affordable housing” doesn’t have to be an oxymoron.

141westville pushed the envelope on a few fronts:

The apartments were smaller than others in the pilot. Nevertheless, it demonstrated the demand for affordable, compact, single living by leasing out its apartments shortly after its recent opening;

It was able to avoid triggering the 4th floor elevator requirement, perhaps because both of the ground floor units are accessible;

It cleverly earned community buy-in before the permitting process even started by hosting 250 on-site tours of a full-scale model apartment that they built on a trailer;

Being located near transit, the project built no off-street parking and only leases to residents who do not own a car.

I am really impressed with 141westville, and would love to see several projects like it take shape in Roslindale. But I think it’s unlikely that we’d see more than a few built anytime soon.

For one, it would be very difficult to finance the development with debt or investor money due to a lack of comps. The 141westville owners were trailblazers who self-funded their project and took on considerable financial risk, in part so that others in the future may not have to. We now have a comp, but I’m assuming we’ll need at least a couple more self-funded passion projects before lenders will hand out reasonable term sheets.

Another key challenge is threading the needle of complying with IDP while keeping the project financially feasible. If not for 141westville’s dogged pursuit of a workaround to the complicated and costly tenant lottery mandated by IDP, their project would have been underwater for 15-20 years.4 What’s worse is that the lottery process itself hasn’t changed, so the next developer will have to face these same issues. If they don’t have the same resourcefulness to find a workaround that the City will accept, their project will likely go unbuilt.

All this is to say that while I think compact living is due for a comeback in Boston, we’re still in the early days.

Won’t my street be flooded with new developments?

No, and here’s why:

Financial incentive. Just because zoning allows a property owner to redevelop doesn’t mean it’s financially worthwhile. If they own a parcel with an older ranch-style home in disrepair? Sure, that could be a good redevelopment candidate. A triple-decker renovated 15 years ago? Not so much.

Slow turnover. Even when the financial incentive to redevelop is there, owner-occupied homes tend to redevelop very slowly.5 This is because people who own their homes generally like where they live and will stay put until they’re good and ready. Redevelopment of condos is especially slow, because multiple owners need to agree to sell at the same time.

As I mentioned in the introduction, S0 zoning could result in 520 additional homes over the next decade, built on about 110 parcels. This represents an 11.5% redevelopment rate.

Let’s visualize what an 11.5% redevelopment pattern looks like on a typical residential street. Pictured below is my block on Farquhar Street with 33 parcels (sadly, we’re just outside of the Squares + Streets area). If 11.5% of them redevelop in the next ten years, we might see four single family homes turn into 6-plexes by 2035, for a net addition of 20 homes and 45 new neighbors.

I don’t know about you, but this doesn’t look like development run amok to me; it looks like the epitome of incremental development. This is how you add gentle density to a neighborhood.

But what about the parking?

Rezoning residential streets for more homes raises two important points related to parking:

More homes = more parking demand.

The S0 does not require off-street parking for new homes.

This might seem like a recipe for overwhelming our street parking supply, but that’s just not going to happen.

If you take the overnight parking demand that comes with 520 new homes, and compare that with residential street parking, then there are enough spaces for all the new cars. This holds true even if developers don’t build a single off-street parking space, which of course they will.

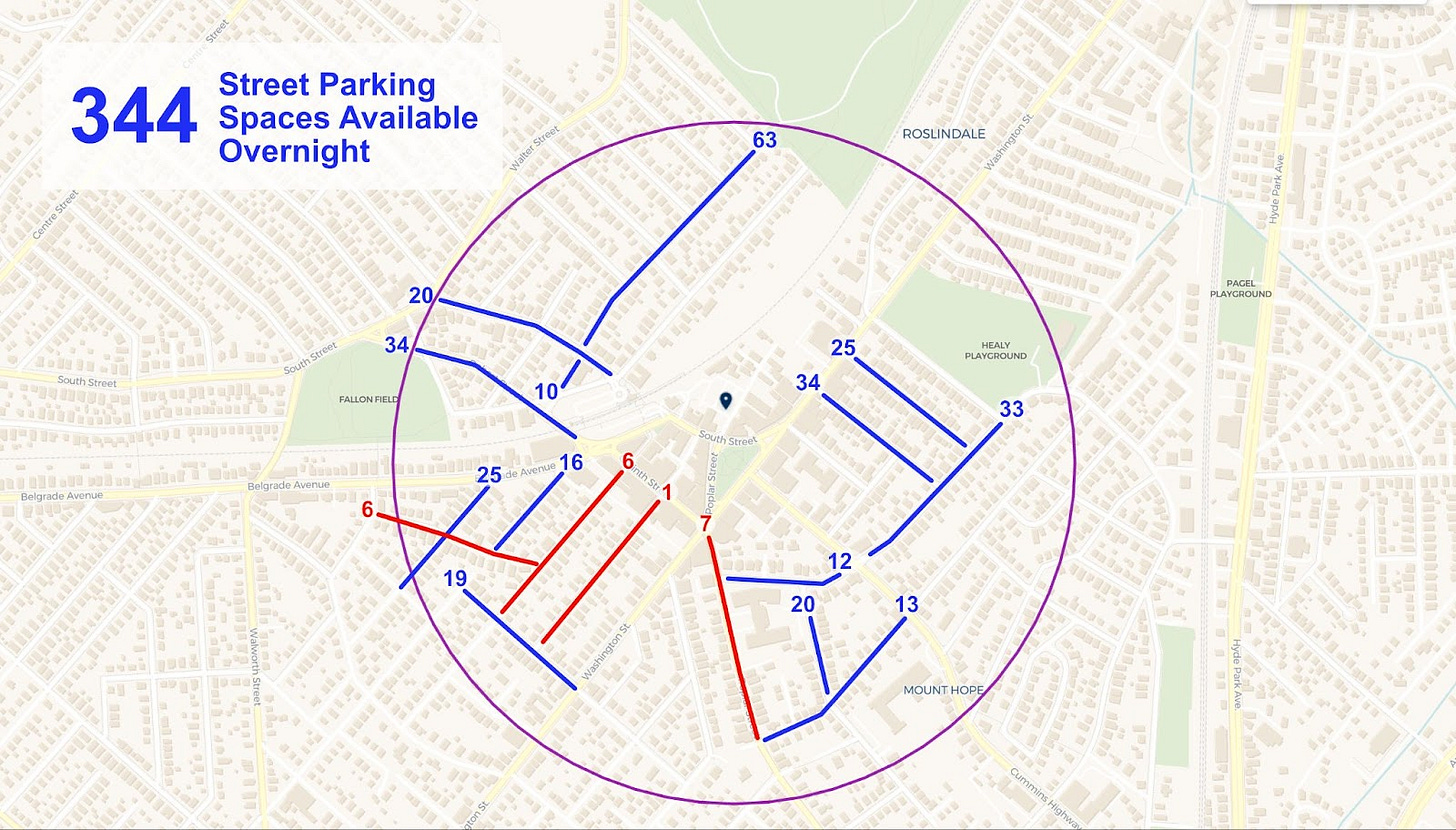

Street parking supply and demand

Boston has one of the lowest rates of car ownership of any metro area in the country. In 2019, the city averaged 0.95 cars/household. For 520 homes, that translates into just under 500 cars.

To figure out if we have enough street parking for 500 new cars, I simply counted the number of spaces available. Peak demand for residential street parking is overnight, so it stands to reason that if there are enough open spaces after, say, 10PM, then our supply is sufficient.

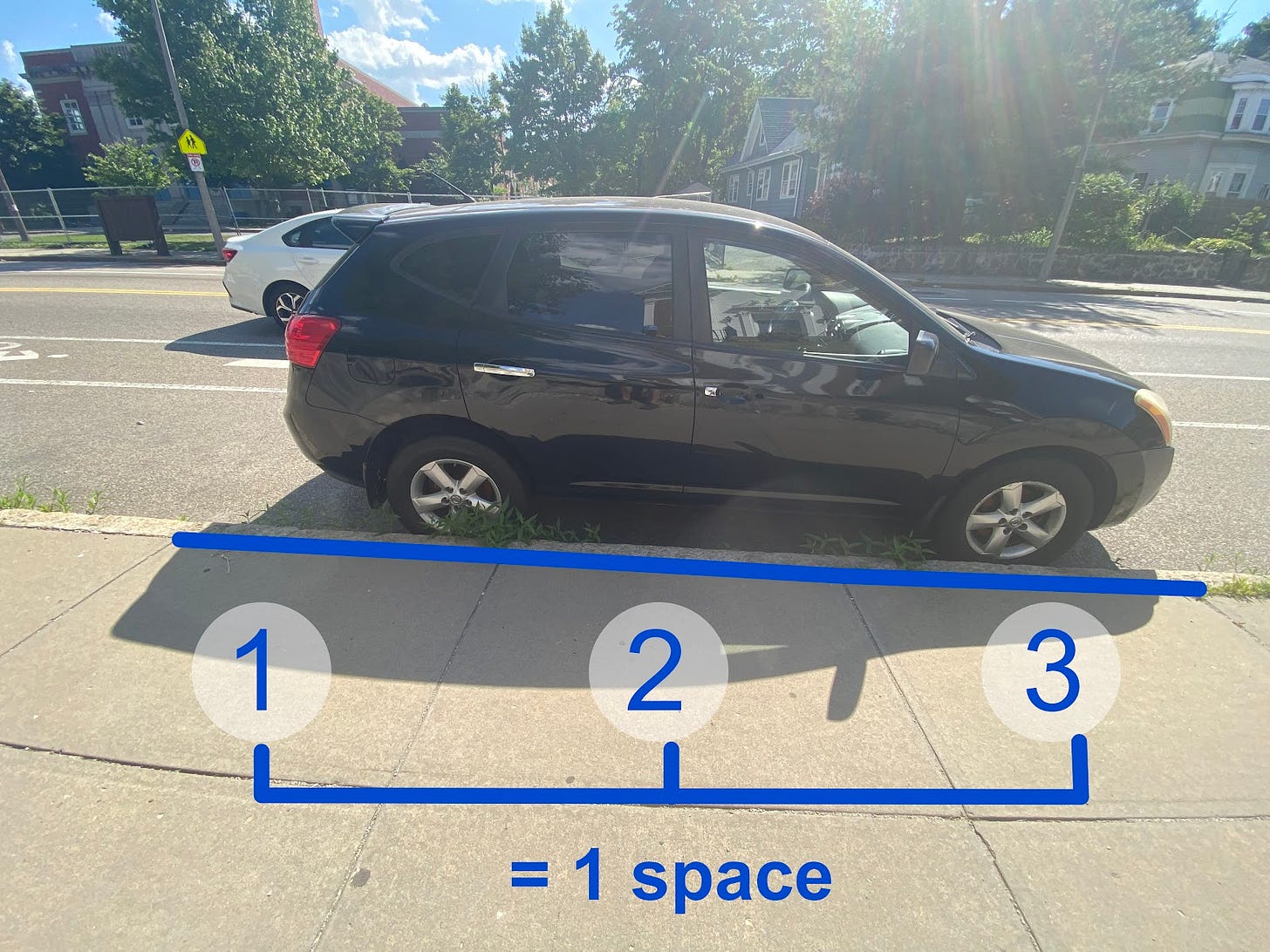

I used sidewalk squares to roughly measure open spaces.

I walked about half (17) of the residential streets in the S+S area on three different nights in June between 10PM and midnight. Following the Metropolitan Area Planning Council’s parking study guidance to document “typical days,” I went out on a Sunday, a Wednesday, and a Friday in June before the school year ended for public and charter schools. For every street with 10 or more open spaces, I walked it at least one more night to make sure the first count wasn’t a fluke. For each street on the map below, I reported the lowest count.6

Again, this is only half of the residential streets in the S+S area. Knowing a bit about the streets I didn’t walk, I think it’s reasonable to expect that they host a similar number of open spaces. So we’re looking at 680 available overnight street parking spaces. Even if you think I overcounted – perhaps I should have used 4 sidewalk squares instead of 3 to count a single parking space – you can lop off 25% from my count and still get more than 500 open spaces.

Long story short: There’s enough street parking, within close walking distance, to absorb all of the new cars.7 And this is before we even consider the hundreds of unused off-street parking spaces in the S+S area. I may write a future post on the parking management best practices we could put in place should it become necessary, but for now I hope that I’ve been able to make a convincing case that we have a glut of residential parking.

The tradeoffs are worth it

At the end of the day, land use planning is about making tradeoffs. Will things look a bit different? Taller? Street parking a bit tighter? Yes, yes, and yes, and that won’t be to some people’s liking. But I argue in the next section that the benefits of upzoning to S0 are well worth the tradeoff of some smaller yards, slightly taller shadows, and at worst a 4-minute walk to your car in the morning.

The benefits of upzoning residential streets

Intrepid researchers and advocates have organized the vast literature on upzoning’s benefits. For our purposes, I’m only going to cover a few advantages, starting with some “What’s in it for me?” benefits, then touching on some key “we” benefits for Roslindale.

Upzoning gives homeowners more property rights

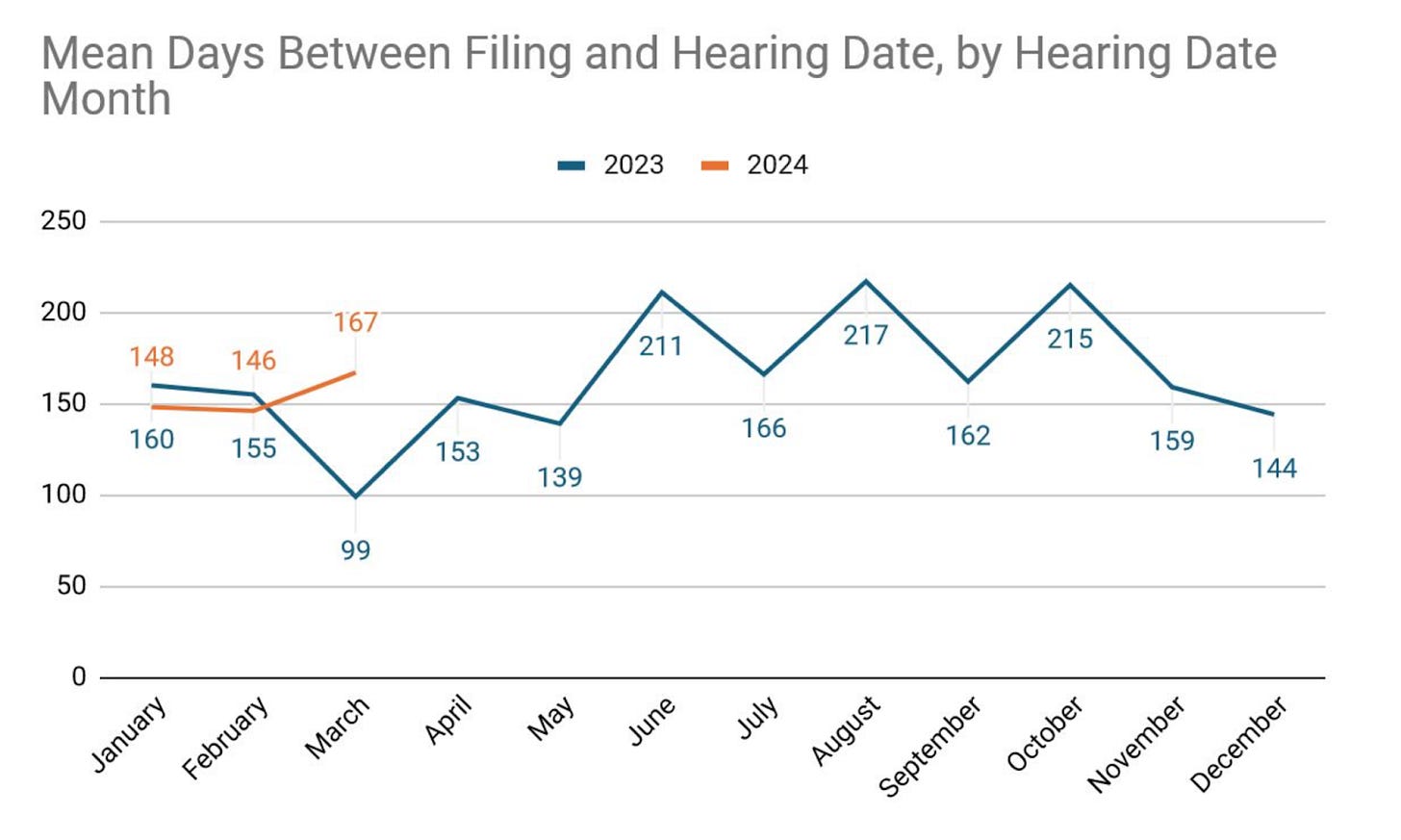

Want to put in a dormer on your third floor? Pop a simple roof on your back porch so that you can still use it when it’s raining? Well, the chances are that you’re going to need to apply for a variance from the Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) to be able to do this. To get your variance, you first need to get the blessing from your abutting neighbors, and then you can wait 5 to 7 months to present your case to the ZBA. Oh, and it’ll probably cost at least a few grand to hire an architect and a lawyer to present plans that in most cases could have been done by a contractor.8

“Wait, what? Why?!” It’s because more than ⅔ of homes in the Roslindale S+S area are out of conformance with the zoning code. In most cases, this happened because after the home was built, the zoning code was updated to be more restrictive, prohibiting uses that had been previously allowed. And when your home is out of conformance, you’ll need to get a variance any time you want to make a significant change to your property.

A powerful side effect of S0 zoning is bringing virtually all homes in conformance with zoning, and much more operating room for making improvements to your property without needing a variance.

I understand that the Planning Department is looking to usher in some zoning relief through its ADU program that may allow for some of the uses I described above. However, I think that updating the base zoning code for residential streets is the most appropriate approach to bringing properties into conformance.

Adding density will slow our property tax increases

You might have heard about commercial real estate’s struggles in the wake of the remote work transition. That’s a problem for Boston, because commercial property tax contributes more than a third of our tax revenue.

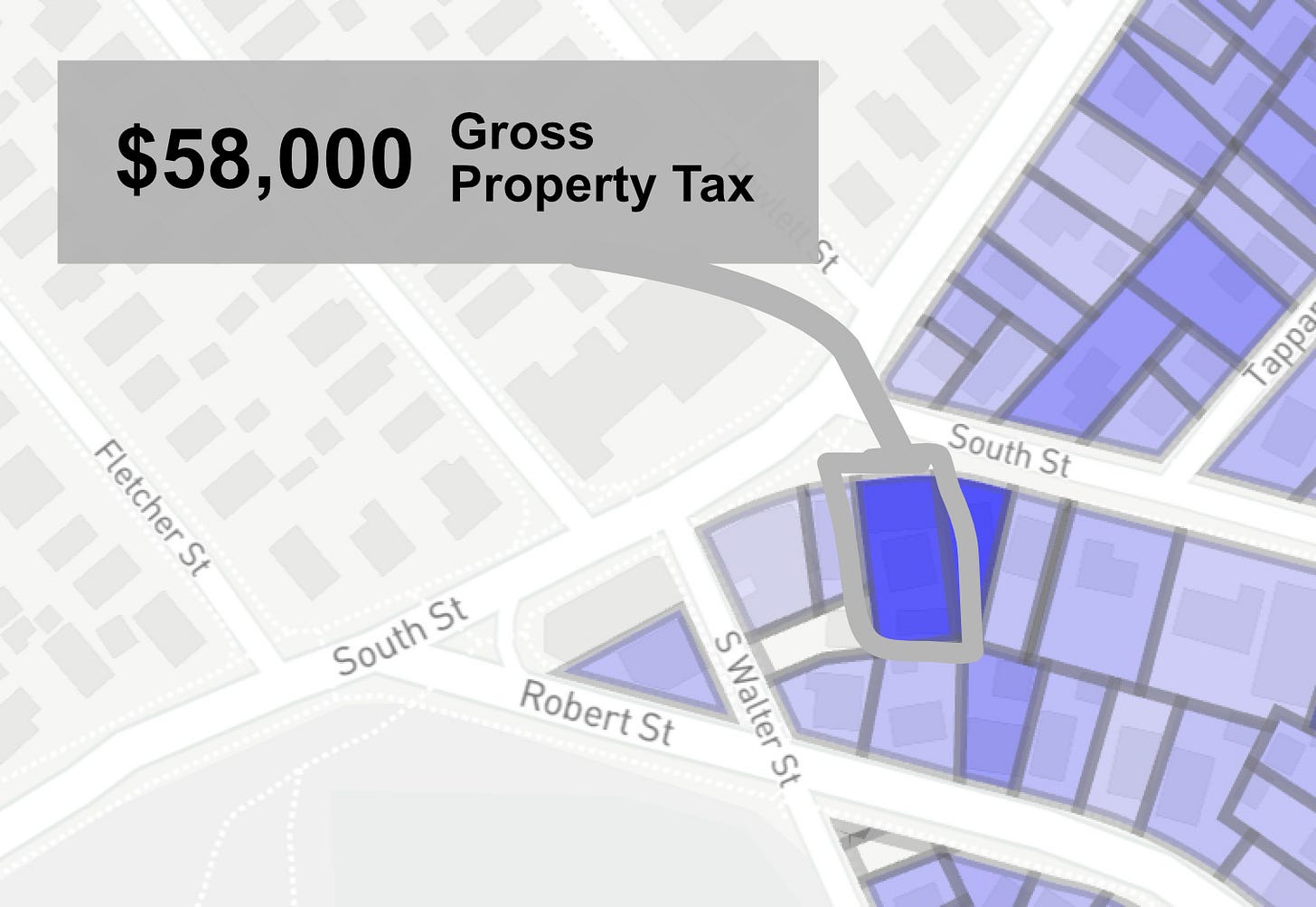

To fill the commercial-sized hole in our tax base, a residential property tax hike is all but inevitable. Allowing more housing and mixed-use development is not the only, or the strongest, tool to slow the coming tax increase. But in the long-term, adding more density will grow our tax base and lighten the burden on individual renters and homeowners.

From a tax revenue perspective, the most “productive” parcels are those with more property on them to tax (i.e., floors, units of housing, workspaces). On the flip side, among the least productive parcels are those with big lots and one or two homes. I’m not bringing this up to shame anyone – I live on one of these “unproductive” parcels myself!

The point is just to recognize that parcels with more homes benefit us all by contributing more tax revenue. For example, on South Street at the edge of the S+S area is a newer 9-condo development. Not only does it fit seamlessly into its neighborhood and add foot traffic to the coffee shop across the street; it’s a relative tax revenue powerhouse!

Of course dense developments consume more city services in total, but they’re still net contributors. Also, nine condos on a single parcel use proportionally less road, sewer, snow plows, etc. than nine adjacent parcels with single family homes.

I’m not advocating for some huge neighborhood redesign for the sake of maximizing the tax base. But I do think that the expected tax contribution for new developments should be part of the discussion, and frankly it’s kind of weird that we don’t consider things like this already. We’re likely entering a new fiscal era in Boston, and allowing our residential streets to fill out a bit is good for the city’s financial health.

More housing and neighbors IS the main benefit

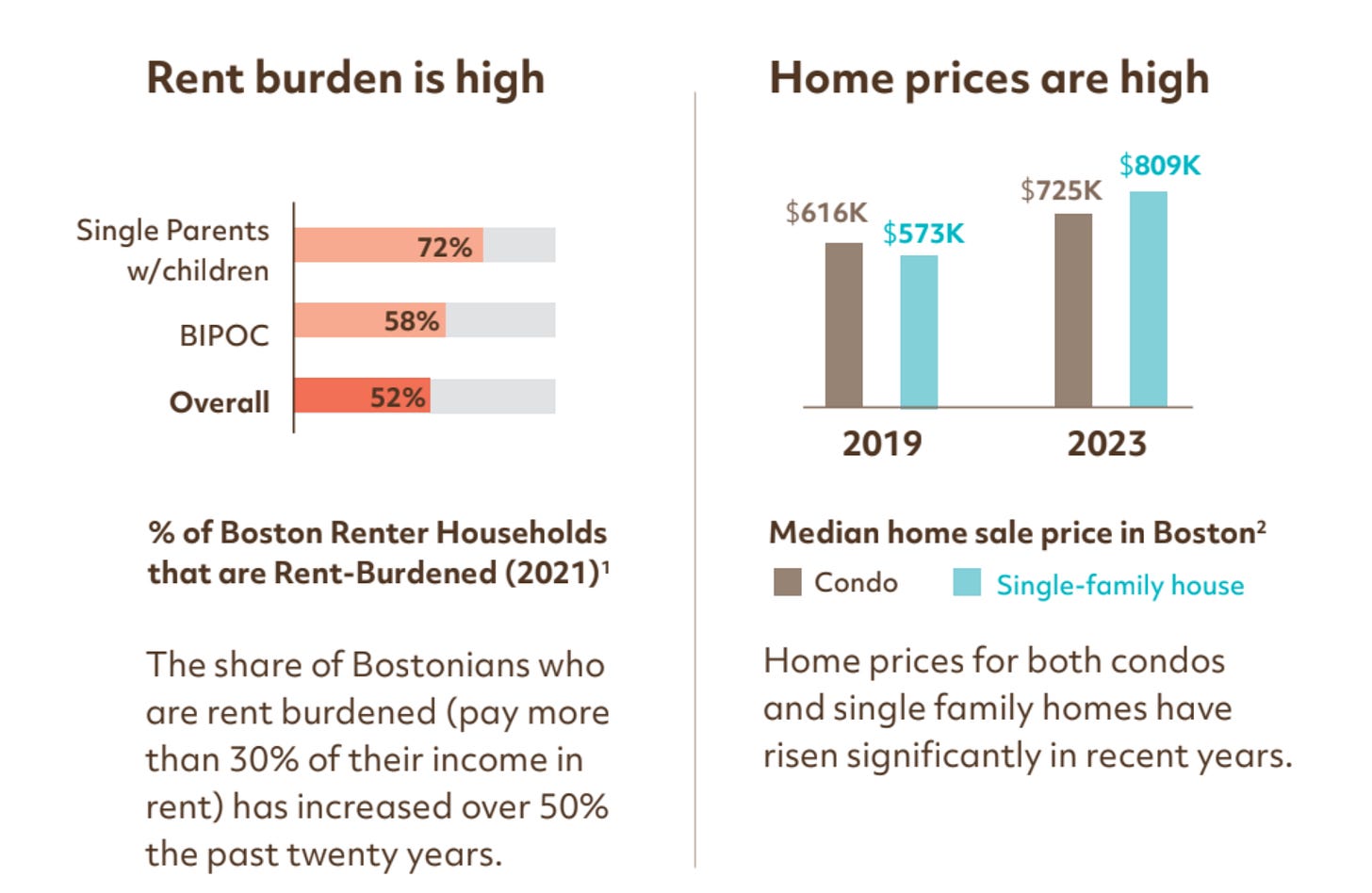

Decades in the making, our current housing crisis has left us short tens of thousands of homes in Boston, and hundreds of thousands across Massachusetts. The consequence of too few homes has been housing costs gone bananas, which devastates renters’ finances and drives out young people and families with children.

We are all worse off for this housing crunch. Our kids can’t afford to move here as they enter adulthood. Our parents can’t afford to retire here. And the workforce serving our community can’t find a place to live nearby.

Building more homes is the most important, if not the only, solution to increasing access to good, affordable homes. This argument can be surprisingly controversial in some progressive circles, so for the supply skeptics out there, please see Exhibit A:

Snarkiness aside, I hope that most of us can agree that the housing shortage is so deep and pervasive that it requires an all-hands commitment to building homes. We shouldn’t flinch at the thought of making room for more neighbors on our residential streets.

Again, what we’re talking about here is thickening to the next increment of density, not becoming the next Manhattan. This will enrich our lives by adding cool new businesses to our streets, more foot traffic to our local favorites, new friends to bump into while walking to the Square, more kids for our schools and playgrounds, and more weekend events to choose from. This is a story of increased neighborhood dynamism, and it makes me excited.

Diverse housing will diversify our streets

At the neighborhood level, Roslindale is relatively diverse across race, income, education, and age.

But if you look under the hood at the three census tracts that make up the S+S area, it’s clear that some parts are more diverse than others.

It’s not a coincidence that the least integrated census tract also has the most homogenous housing stock (Full disclosure: I live there!).

The good news is that S0 zoning can reduce street- and block-level segregation by allowing more housing types to flourish. In his review of Greater Boston zoning regulations, BU economist Matthew Resseger found that blocks zoned for multifamily housing have 9% more Black and Hispanic households than adjacent blocks zoned for single-family homes.9

Assuming we can agree that it’s important to encourage racial and economic diversity at the block level — especially for kids10 — then we need to take diversifying our housing stock seriously. In particular, we’d do well to feather in more multifamily rentals and affordable housing of the type that S0 would allow.

Rental housing will add to our social fabric by making space for people who might not be in a position to buy here: our workforce, young professionals, and young families.11 It will also (ultimately) provide relief to Roslindale’s beleaguered renters, 34% of whom spend at least a third of their income on rent. In the wealthiest census tract above, more than 41% are rent-burdened.

As for affordable housing, Roslindale could stand to add more. Currently, 13% of our housing stock is affordable. This is higher than the state’s minimum 10% threshold, but well below the city average of 19%. While Boston should be commended for having the highest percentage of affordable housing of any major American city, this accomplishment is dulled a bit by the fact that 73% of it is in high-poverty areas. It really matters where affordable housing is built.

I’m a member of the Longfellow Area Neighborhood Association, which has championed a Habitat for Humanity project to convert a blighted vacant property into 4 affordable homes, one of which is fully ADA-compliant. It’s a great project in a highly desirable area, with the Roslindale Wetlands in its backyard and the Arboretum a block away. Let’s do more of this!

To be sure, street-level diversity isn’t enough for integration to occur. But it is a prerequisite.

Upzoning will diversify our developers and building styles

A complaint that I share with many growth-resistant neighbors is that housing development in Boston, like everywhere else, is dominated by huge players that seem to be addicted to building apartments that all kinda look like this…

But let’s reflect on how this situation came to be.

One key reason we have so few players is that our zoning code makes it really hard for small developers to thrive. For one, the code prohibits the small multifamily housing I’m arguing for throughout much of the city. Secondly, the code is 3,800 pages long, full of complicated district overlays and contradicting terms. And finally, by default, if not by design, the code requires that most new developments go through a variance process.

In other words, the code’s a mess, so any developer will need deep pockets to pay for a good zoning lawyer to carry their project through the lengthy approval process. “Paperwork favors the powerful,” writes Jen Pahkla in her book Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better.

Fortunately, we’ve got a remedy! By making zoning compliance less complicated and expensive, which the S0 does, more people get to play. This creates an opening for smaller and more diverse builders to have a hand in shaping the growth of our city. I think that’s going to result in some interesting ideas for our built environment.

If we want to see a greater variety of home builders and styles in the next 10-20 years, we first need to legalize more forms of housing in our zoning code.

Upzoning will make us more climate resilient

In the not-so-distant future, the combination of sea level rise and more numerous, violent storms will bring consistent flooding to the low-slung coastal neighborhoods. A patchwork effort is underway to make these areas more resilient to severe flooding, but it’s looking unlikely that we’ll build enough infrastructure in time to stave off some of the damage to come.

This new normal will suck for the people who live and work there. It stands to reason that a couple of severe incidents will inspire many to move elsewhere. The question becomes: where will they go? Do we want them to stay here, or take their families and their talents out of town? And what happens to Boston’s future as a city of consequence if they leave?

I would much rather see them stay in Boston, and that’s going to require that we make some room. Adding flexibility to the zoning code, particularly in areas safe from sea-level rise, will strengthen the City’s ability to plan for these future internal migrants.

Conclusion

The Boston Planning Department’s mission is to advance resiliency, affordability, and equity across the city. I’ve tried to present a practical and principled case for why rezoning residential streets touches on each of these goals, but I want to linger on equity for a moment longer.

If we are going to equitably address our housing crisis, then it needs to be everyone’s job to welcome greater density. That includes our residential streets. It would be unwise and, frankly, unfair to saddle our commercial streets with sole responsibility for this challenge.

Obviously, solving the housing crisis is bigger than what we can accomplish in this ⅓ mile dot in Roslindale. But as one of the first of what may be 18 S+S areas throughout the city, Roslindale is a pacesetter for the overall initiative. What happens here can also set an important precedent for the broader revamp of Boston’s zoning code in a few years’ time. I’d like to see us make the most of this opportunity.

Note that the second character in S0 is a zero.

Here’s the the method I used to calculate this 10-year housing projection. Huge thanks to Perci PBC’s Eric Ouyang for developing it.

I calculated the population estimate by multiplying the housing projection of 520 additional homes by Boston’s current average people per household of 2.26 per the US Census Bureau.

Small income-restricted buildings with 4-14 homes are not uncommon in Boston; they make up 14% of the City’s affordable development projects. According to the City’s Income-Restricted Housing Inventory, there are 1,491 affordable housing developments in the city; 144 have between 4-14 rental units (9.65%), and 68 have between 4-14 ownership units (4.56%).

Rather than the City managing a centralized lottery process for affordable housing units, IDP requires that each developer run its own lottery for every development project with mandated income-restricted units. Carrying this out requires hundreds of hours of administration, and so most small developers hire a consultant to manage the process for them. In 141westville’s case, this would have cost $30,000 to manage the lottery for its two officially designated affordable units, plus an annual recurring fee of $3,000 to maintain the waitlist and keep applicants up to date by mail.

Ironically, the income-restricted units were required to charge a higher rent than their market rate units, ($790 vs. $750/month). 141westville was able to provide naturally affordable housing by choosing a lower return on their investment. With a razor thin profit margin, the lottery administration cost was such a burden that the owners were considering whether to increase the rent on the other apartments by 15%, or to just leave the income-restricted units vacant. It’s a relief that they ultimately reached a resolution with the City, because those are two terrible alternatives.

Roslindale has a much higher rate of owner-occupied homes (53.4%) relative to Boston as a whole (34.8%)

If interested, I documented my partial parking study. In addition to the counts, I took some photos and jotted some observations.

Some of these streets are resident permit parking only, but anyone in Roslindale can get a free resident permit parking sticker with a 5-minute application.

Sara Bronin’s report Reforming the Boston Zoning Code, commissioned by the BPDA, includes this banger on pg. 17: “A homeowner who wishes to put a gabled dormer on a roof or a small business owner who wants to add a takeout component to their restaurant may pay $10,000 and undergo a six-month review process to achieve what in other places might have a one-day approval turnaround time and cost less than $100.”

Underscoring the point that the zoning process requires homeowners to incur often unnecessary professional service fees, see the exchange from the pro-housing group Discord between two veterans of the zoning appeal process, one of whom is an architect:

Member 1: “Well, you need [RE attorney name redacted] ($600/hr) and your architect ($400/hr) to present to [local zoning board of appeals], so that's a thousand bucks for the hour. And before that the architect has to draw up 3 versions of your plans detailing the different plantings, fenestration, siding styles, etc…A lot of these types of projects you could just have a contractor do otherwise.”

Member 2 (the architect): “this is huge tho, so many people who don’t really need an architect need an architect in boston for renovations.”

I want to be careful not to oversell zoning’s part in this multi-factor story. It’s certainly not the only driver behind differences in housing stock and demographics across these census tracts. After all, they mostly share the same zoning (2F-5000). However, it’s notable that the green tract does have a chunk of 3F-4000 zoning, which contributes to its much higher proportion of multifamily housing.

Harvard economist Raj Chetty’s groundbreaking research into the Moving To Opportunity voucher program found that providing low-income families with vouchers to move to higher income areas resulted in significant benefits to the children of those families, especially if they were young at the time of the move. They found that every year spent in a lower poverty neighborhood during childhood increased their earnings as adults. “More broadly, our findings suggest that efforts to integrate disadvantaged families into mixed-income communities are likely to reduce the persistence of poverty across generations.”

While I advocate here for prioritizing the growth of our rental stock, I believe that increasing home ownership for the historically disadvantaged is essential. The State Legislature’s Black & Latino Caucus reports that Massachusetts’ homeownership rate is approximately 37% for people of color, compared to 69% for white households. This chasm of housing inequality, rather than income inequality, may well be the single greatest factor driving the wealth gap between races.

A centralized lottery process makes a lot of sense and not just for the low rent development at 141westville. Lottery costs are a burden and there are ways to lessen that burden without abridging fair housing.