In the last post, I shared how the Rozzie Square Small Area Plan provides a lot to be excited about for those who want more housing, business dynamism and walkability in our neighborhood.

But in a 120-page plan with something like 50 proposals – there were bound to be some areas where our visions don’t align. So for what it’s worth, I’m sharing those below.

Before diving in, I’ll add my usual disclaimer that these takes are not informed by a long career in urban planning or design. Wherever you notice any errors or wrong assumptions, please let me know.

Land Use & Design Framework

My biggest disappointment is the Plan’s refusal to allow for the next increment of housing density in most residential areas.

Few residential streets around the Square will be rezoned under the Squares + Streets initiative. Instead, they’ll be addressed with more modest zoning initiatives like Neighborhood Housing.

I appreciate that the Planning Department is trying to strike a balance between the two competing community visions for land use. But I strongly disagree with lowering our ambitions for residential street rezoning. Boston is short of tens of thousands of homes, and lower density areas are the best, most equitable places to target more housing.

This is a miss, and I encourage the Planning Department to revisit the idea of rezoning residential areas in the final Roslindale Square Small Area Plan.

There are two main problems with leaving residential rezoning up to the Neighborhood Housing initiative:

Its timeline doesn’t match the urgency of the moment. Currently, only large properties (60’ wide or more) have been assigned a target timeline of “2025.” Most parcels in Roslindale and elsewhere won’t be affected by this first phase. It appears that medium and smaller properties will be rezoned 2026, or later. We need to do more, and we need it a lot faster.

Its scope is decidedly modest. The plan notes that any future residential rezoning will “reflect existing built patterns” and “affirm existing scale,” i.e. bring existing buildings into conformance with zoning rather than bumping up to the next increment of density. While re-legalizing the triple decker is a good thing, that just brings us back to where our things stood in 1924. It’s a fundamentally retroactive approach.

We need a proactive approach to thicken up all areas of the city, and especially in our lower density, high demand residential areas. A few ADUs here and there isn’t going to cut it.

Rather than our current slow and piecemeal approach to rezoning, I’d like to see Boston follow the example of peer cities like Minneapolis, Portland, and Austin, and implement broad citywide residential rezoning.

The Design Guidelines are a bit too prescriptive. I generally disagree with enforcing subjective aesthetic preferences.

Example 1: Creative sensitivity

The Design Guidelines call for creative sensitivity toward sites that are “culturally, historically, or architecturally significant…New development that is adjacent to these sites must demonstrate sensitivity and creative responsiveness in their massing, facade composition, and material palette. Redevelopment of or additions to these sites should try to maintain significant character defining features through adaptive reuse rather than demolition."

Is it necessarily a good thing to mandate this kind of creative sensitivity? I lived in India for a couple of years, and at least where I spent my time, it was common to see very old structures next door to brand new ones. The new buildings usually paid no mind to the facade composition or material palette of their elder neighbors. It took me some time to get used to this juxtaposition of old and new – mainly because I come from the land of design buffer zones. But once it became familiar, I came to like it a lot. Now, you may strongly dislike this lack of creative sensitivity, and that’s totally fine. The point is that your preference, like mine, is subjective. It’s not, as far as I know, some universal principle of design, and so we shouldn’t be using regulations to enforce it.

More importantly, I can just see the costs ballooning for any development that dares to build next to a “significant site.” Except in rare instances, I don’t see how saddling developments with these aesthetic requirements is worth the tradeoff of fewer, more expensive homes and commercial spaces.

Example 2: Relationship to Context

The Design Guidelines call for breaking up the massing of new buildings with upper story setbacks to ensure adequate air flow, sunlight, and comfort.

Upper story setbacks may seem like a sensible design tweak, but they come with real drawbacks. They meaningfully increase the cost of construction and building maintenance, they increase a building’s embodied carbon and operational carbon emissions, and they reduce its occupiable space (and hence restrict housing supply). They also under-deliver on their purported benefits, especially for small- and midsize buildings. The end result is inefficient, and often less attractive, urban design.

Wind tunneling, as I understand it, is only a real concern for buildings above 20 stories. Further, wind can be addressed through other means like street trees and ground-level spacing, which the Squares + Streets zoning districts already tackle.

While upper-story setbacks do increase solar access, this may actually be counterproductive in a warming world where shade is valuable. I’ve written about how we need a lot more shade in Rozzie Square. For me, the relief that a building’s shadow would provide on hot summer days outweighs the downside of a shorter window of sunlight. And as they do with wind, the Squares + Streets zoning districts partially address solar access by requiring deeper ground-level setbacks than what current zoning allows.

Finally, the argument that upper story setbacks improve design by breaking up “visual bulk” is suspect. I don’t know of any material evidence indicating that bulk is actually a negative in urban environments. Indeed, most of the urban environment is made up of simple boxes, and it looks pretty good.

As with the example of creative sensitivity, I don’t have a problem with upper-story setbacks per se. But I do have a problem with using regulation to enforce aesthetic preferences.

Having seen many examples of historic preservation weaponized to prevent housing redevelopment, I’m concerned about the planned inventory of Roslindale’s “potentially historic” structures and how that might be used to delay or block worthwhile redevelopments.

The Plan notes that the Boston Landmarks Commission will take 2-3 years to complete an update of Roslindale’s Area Form.

I suspect we’ll see an uptick in citizens' petitions to landmark buildings in the Square in order to block redevelopment of older buildings, or to make it prohibitively expensive.

My admittedly radical belief that most historic preservation is bad stems from my conviction that cities should function more like organisms than museums. I think that most people would be surprised to learn just how much of an impact that preservation policy has had on the volume and cost of building in Boston. And on learning how it is applied, many would agree with writer Ian McGregor’s assertion that, “[i]n practice, historic preservation policies are often overly broad and dictated by arbitrary political whims.”

So I don’t know, maybe we could, like, skip the Roslindale Area Form update or something? A boy’s gotta dream.

Housing & Real Estate

Requesting a higher proportion of 2+ bedroom Inclusionary Zoning units is probably counterproductive to keeping more families in Roslindale.

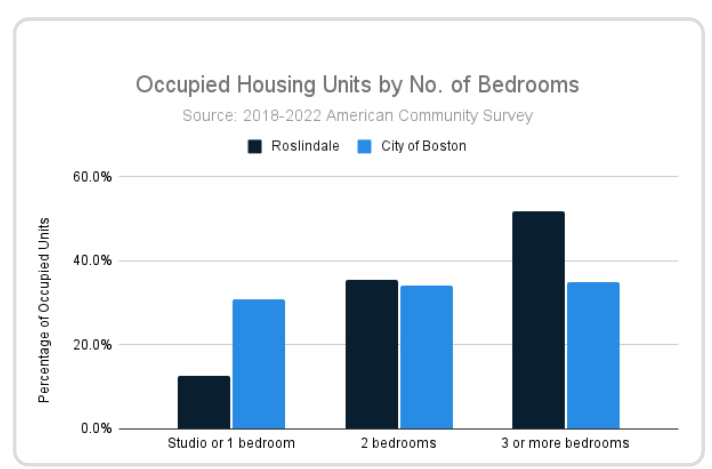

The Planning Department’s study of neighborhood demographics found that Roslindale is home to a higher percentage of children than the city average. They concluded from this that we should encourage the construction of larger units (i.e. 2+ bedrooms) to house more families with children.

My interest in housing policy started with a desire to slow the exodus of families with children from the city. I care deeply about strengthening Roslindale’s reputation as a family-friendly neighborhood.

That said, I fear that “requesting” (is the request a de facto requirement?) residential developments to set aside more large units for inclusionary zoning may backfire.

For those unfamiliar with Boston’s Inclusionary Zoning (IZ): As of October 1, 2024, all new buildings with seven or more homes must income-restrict 17-21% of those homes for folks earning below the area median income. This is an increase from the previous requirement of income-restricting 13% of homes in buildings with ten or more total homes. IZ is many things, including an entrée to mixed-income living, which I wholeheartedly support. But financially speaking, it’s a tax on residential developments.

Anecdotally, the IZ tax is already affecting the housing development pipeline, especially small-to-midsize multifamily. Several Boston-based residential developers have shared that they’re looking to build outside of the city, citing the increased IZ requirement as a significant obstacle to making new projects financially viable. It’s worth noting that while Boston increased its income-restriction requirement, other cities are reevaluating theirs. Even San Francisco, an infamously difficult city to build in, rolled back its inclusionary zoning requirement in 2023 from 22-33% down to 12-16% in order to spur more home building. There’s a growing body of evidence that unfunded inclusionary zoning hurts project feasibility and makes the resulting housing more expensive (see here and here).

Requesting builders to set aside even more of the largest/most valuable homes for income-restriction will increase this tax on residential development.

While the IZ set-asides may result in some new affordable 2+ bedroom units, it will come at the cost of broader affordability. This is because making projects more expensive results in fewer homes getting built, and those that are built will charge more for the market rate units in order to offset the higher cost.

Finally, is prioritizing more 2+ bedroom units actually what's called for here? I’m not sure if that’s the right conclusion to draw from the demographic data. Yes, we have a higher proportion of children relative to the rest of the city. But that’s at least partly due to Roslindale having more 2+ bedroom homes relative to the rest of the city.

Instead of intensifying an already-challenging homebuilding tax, the Planning Department should adjust this proposal to maintain consistency with the existing policy to make income-restricted unit types that are proportional to the overall project.

Small Business

Given the other demands placed on developers to support local businesses, asking them to make additional donations to business support organizations is excessive.

Projects that go through the Article 80 development review process (i.e. buildings with 15+ homes or 20,000+ Square Feet) will be asked to donate to local business support organizations.

Taken in isolation, this proposal seems sensible. But larger developments will already support local businesses by building ground floor active use spaces, which are required for Squares + Streets zoning districts S3 and above. Also, the City’s upcoming anti-displacement plan will require that any redevelopment project give at least 6 months advance notice of any displacement, and is contemplating requiring developers to provide displaced businesses with technical and financial assistance in relocating.

Exactions on developers should be directly related to the project itself, because again, taxing new development isn’t free money. Much of the added cost will ultimately be borne by future tenants.

I agree with this suggestion from Perci’s Eric Ouyang: “Support for local businesses should instead be funded in a predictable manner through the City's operating budget, rather than on an ad-hoc basis that’s dependent on future development.”

Ok, I’m done complaining! I’ll just close by reiterating that I’m overall bullish on the draft Small Area Plan. It has a lot of promising proposals to strengthen our neighborhood.

That said, I encourage anyone who made it this far to push for a final Plan that truly reflects the urgency of the moment and sets a precedent for the kind of forward-thinking urban policy our city deserves. By embracing more ambitious rezoning, reevaluating counterproductive regulations, and ensuring that policy aligns with development feasibility, we can create a thriving, equitable Roslindale that meets the needs of current and future residents.